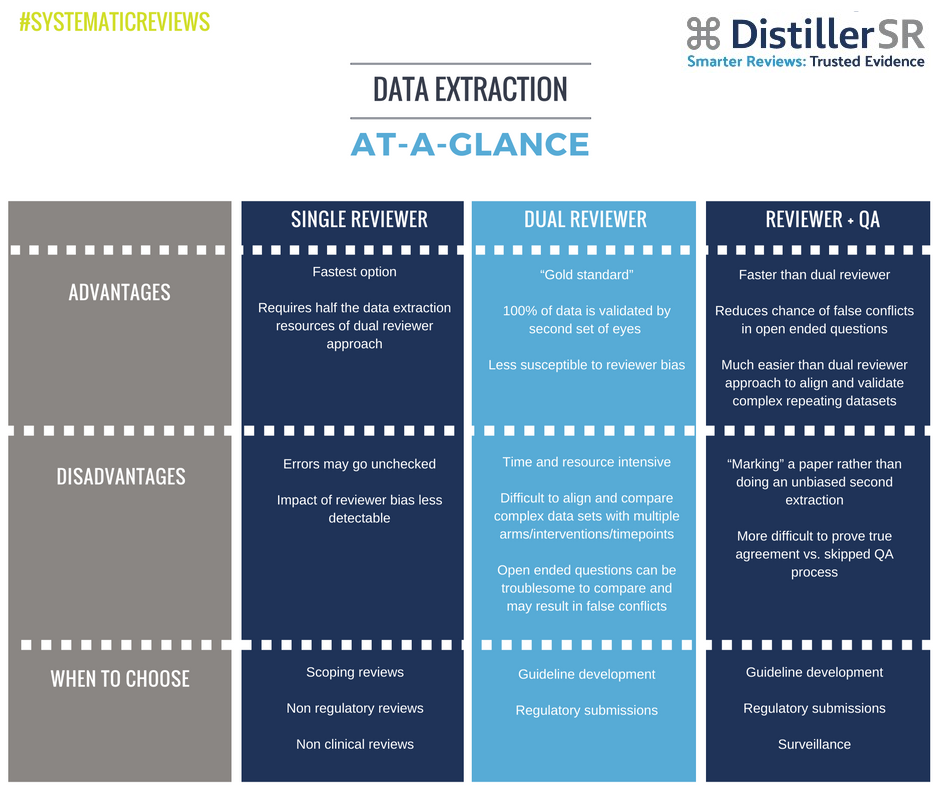

Efficiency and rigour are often competing priorities in the systematic review process, and achieving both without sacrificing either is a challenge.

When it comes to the data extraction step of a systematic review, most of the groups we work with use one of three approaches: single reviewer, dual reviewers, or a reviewer-plus-quality-assurance (QA) combination. Several factors typically influence the group’s choice, including the purpose of the review and the time and resources available to complete it. In my experience, the decision usually comes down to efficiency versus rigour, and where that balance must lie.

Single Reviewer

The simplest way to approach data extraction is to have a single reviewer who extracts data from each reference. It’s faster and much less resource intensive than any other method, which makes it an appealing choice, particularly for scoping reviews or any non-regulatory, non-clinical review project. A single reviewer approach, however, is missing the “sanity check” of a second set of expert eyes on the material to catch errors and mitigate any reviewer bias. For this reason, it may not be appropriate in all circumstances.

Dual Reviewers

Adding a second reviewer to the data extraction process is one way to increase the rigour of the systematic review, but it also doubles the resources required at data extraction. In this approach, two reviewers extract data in parallel and then compare answers to ensure consensus.

Dual reviewers are often used when the systematic review is being conducted for guideline development, regulatory submissions, or any purpose that would necessarily put rigour ahead of efficiency. While a dual reviewer approach is considered the “gold standard” for data extraction – and may actually be a methodological requirement, depending on the purpose of the review – it takes more time and discipline than the single reviewer approach.

Complex, repeating data sets and open ended questions captured by multiple reviewers are especially difficult to match up and compare accurately when using the dual reviewer approach. Tools exist to make this easier, but it does require close synchronization to work well.

1 Reviewer, 1 QA

In this hybrid approach, one reviewer completes the data extraction, followed by a second reviewer who goes through the data collected by the first person and validates it, making comments and corrections if needed. References do not pass from the specific data extraction stage until discrepancies have been resolved.

The QA approach has a number of advantages over the single or dual reviewer options: it’s likely to be less susceptible to errors or reviewer bias than a single reviewer approach, it is faster than dual screening, it returns fewer false conflicts (when two reviewers enter the same information, but slightly differently), and it is much easier to sync data where complex repeating datasets are present. It’s not perfect, though.

Without an unbiased second extraction, it’s more difficult to prove true agreement (i.e. how do we know for certain that each entry on the form was properly QA’d?). In addition, there’s always the chance that the QA reviewer was influenced by the decisions made by the other reviewer – a little like leading the witness.

Which is best?

Of course, there are other approaches to data extraction, but they are usually minor variants or combinations of the options described above. For example, many groups do dual data extraction on a subset of references to ensure quality and reviewer calibration. Other groups perform QA on a subset of extracted data as a quality check in both single or dual reviewer situations. In fact, we’re increasingly seeing reviews with some level of QA built into the methodology regardless of the overall approach taken.

Ultimately, however, there is no one size fits all solution. Each approach offers advantages and disadvantages that must be weighed against the review’s specific purpose.